- Home

- Keith R. A. DeCandido

The Art of the Impossible

The Art of the Impossible Read online

“This Will Get Out of Control Quickly,” Vaughn Said.

“The minute either Zarin or Worf decides that things aren’t going right, that one will call in the cavalry, and five minutes later, the other one will call in his, and this whole thing will blow up in our faces.”

“We need to call in reinforcements,” Garrett told Captain Haden. “We’ll be a sitting duck if those fleets decide to go at it.”

“Too risky,” Haden said. “I don’t disagree with you, Number One, but Monor and Qaolin already have their bowels in an uproar because I let the Hoplite out in the first place. They’re keeping a close eye on us.”

Curzon Dax shook his head. “What we need to do is put our cards on the table and call their bluff.”

“That’s a quaint metaphor,” Vaughn said. “But I doubt they’re bluffing.”

“I’m sure they think that, too—and will continue to do so, right up until they have to actually play their cards. But one reason why I think they’ve assembled these fleets in the first place”—Dax looked at Haden—“assuming they have assembled the fleets, is because they’re far from home. Reinforcements beyond whatever they’re hiding behind cloaks or in nebulae are days away, and probably not easily diverted. I’m not sure either Zarin or Worf will be willing to start something they can’t finish.”

“I’ve read the transcripts of the meetings so far,” Vaughn said. “I haven’t seen anything to indicate that either side is going to budge. Where does that leave us?”

“I have no idea where it leaves you, Lieutenant, but it leaves me with the winning hand. I just have to play it.”

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

An Original Publication of POCKET BOOKS

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2003 by Paramount Pictures. All Rights Reserved.

STAR TREK is a Registered Trademark of Paramount Pictures.

This book is published by Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., under exclusive license from Paramount Pictures.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN: 0-7434-6406-0

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Cover design by John Vairo, Jr.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com/st

http://www.startrek.com

When I started this book, a child was born in New York City. When I finished it, seven brave men and women died in the sky over Texas. Both served as sharp reminders of the cycle of life and death that is, in many ways, the theme of the novel you are about to read.

With that in mind, this book is dedicated to the child, Benjamin Palmieri, the Space Shuttle Columbia, and the men and women who crewed it.

“Politics is the art of the possible.”

—Otto von Bismarck, 1867

“What God is he writes laws of peace, and clothes him in a tempest?”

—William Blake, America: A Prophecy, 1793

Historian’s Note

This story commences in 2328, thirty-five years after the presumed death of Captain James T. Kirk aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise-B in Star Trek Generations. It concludes in 2346, eighteen years before the launch of the Enterprise-D in “Encounter at Farpoint.”

Prologue

On High My

Spirit Soars

A World in the

Klingon Empire

The boy could taste the scent of the lIngta’ on the wind.

“You smell it, don’t you?” Mother whispered, a proud smile on her face as they knelt in the underbrush. All three moons were out, casting the plant life and the ground in an eerie white glow. Mother held a gIntaq spear in her left hand. The boy was unarmed—Mother was teaching him to track prey in the hope that one day he would be able to hunt on his own. It was their fifth trip into this preserve, and their second at night.

“Lead me to it,” Mother said.

Nodding once—an economy of movement was necessary to keep from being detected by the prey—the boy moved quietly through the underbrush. He could not hear Mother moving behind him; indeed, he only knew that she was there because of her scent.

When Grandfather purchased the land on this world, he had declared this area to be hunting ground, and had imported several types of game animal from all across the Empire and beyond, including a dozen lIngta’ from the Homeworld. The boy had improved his tracking skills with each trip, and he eagerly awaited the day he would be allowed to wield the gIntaq and take the beast down.

Within minutes, he sighted the lIngta’, bent over a stream, lapping up water.

He stole a glance back at Mother, who did the last thing he expected—though it was something he’d been dreaming about for weeks. She pressed the haft of the spear into his left hand.

Eyes wide, he looked down at the gIntaq, then back up at Mother. She simply nodded.

Grinning so widely he thought his cheeks would fold over his ears, the boy turned and got into the proper crouch for throwing. He aimed the spear along the line of his right arm, just the way Mother had taught him. Then he cleared his mind the way his older sister had told him he needed to in order to focus entirely on the prey. Nothing else mattered, not the ground, not the darkened sky, not the three moons, not Mother, not the bush—nothing but the spear and the lIngta’.

With all the strength he had, he threw the spear.

At the age of five, said strength was not much. However, he made up for it in precision. The metal tip of the spear penetrated the lIngta’ directly in its crown. The beast fell to the ground.

The need for stealth now past, both the boy and his mother ran toward the stream. The animal was still alive, but bleeding profusely from the wound in its head. It lay next to the stream, legs twitching. Mother snapped its neck.

Placing a hand on the boy’s shoulder, Mother said, “Your first kill, my son. Be proud—today, at last, you are a hunter. You have taken another step on the path to becoming a true warrior.”

The boy proudly replayed those words in his mind over and over again as he carried the lIngta’ corpse across his shoulders back to the tent where Father awaited them both.

“You have brought dinner, I see,” Father said in his usual booming voice—one of many reasons why it had been Mother, rather than Father, who taught him how to hunt. Father would stomp through the underbrush and scare away every game animal for three qelIqams around within minutes of his hunt commencing.

However, few compared to Father when it came to preparation of the food. Over the next hour, he showed the boy how to skin the lIngta’, the best way to strip the meat from the bone, the proper removal of the head, and so much more.

As they feasted on the lIngta’ while sitting around a fire that was more for warmth than illumination—it barely provided more light than the three moons and the stars—the boy turned to his parents and asked them for a story.

“A new one,” he said. “One you’ve never told before.” It was a bold request, but he felt he had earned the right to be bold after his first hunt.

Father threw his head back and laughed, his voice echoing off the trees and hills. “Very well, my boy, you shall have your wish.” He gnawed on a piece of lIngta’. “Shall we tell him of Kahless and Lukara at Qam-Chee?”

“I know tha

t one,” the boy said impatiently.

“Perhaps the tale of the victory over the Romulans at Klach D’Kel Bracht?”

“I know that one, too.”

“Or maybe Captain Kang’s victory over the creature that fed on warfare?”

The boy knew now that his father was stringing him along. “I know that one, too. A new story, Father!”

Again, Father laughed. Mother said, “Tell him of Ch’gran, husband.”

Blinking, the boy said, “I do not know that one. What is Ch’gran?”

Father swallowed a gulp of stream water from his mug before commencing.

“Over a thousand turns past, after the time of Kahless, the Homeworld was attacked by the Hur’q. Fierce marauders from beyond the stars themselves, they plundered what they could take and destroyed what they could not plunder.”

“They took the Sword of Kahless,” the boy said impatiently. “You’ve told this story before, Father. I know this.”

Smiling, Father said, “And do you know what happened next?”

“I—” The boy hesitated. Whenever Father or anyone else had told the story of the Hur’q, it ended with their disappearance, having devastated the First City and taken dozens of artifacts, including Kahless’s bat’leth.

“Well?”

Lowering his head, the boy said quietly, “No, I do not.”

“Then listen, child, and learn of our people. After the Hur’q left, a great warrior named Ch’gran urged our people to move to the stars—for only by conquering space could we truly become strong, only by taming the stars could we be all that Kahless promised, and only by expanding beyond our Homeworld could we hope to avenge ourselves upon the Hur’q. Besides, we had lost so much to the Hur’q that our best course of action was to find new worlds to provide the resources that the Hur’q’s pillage had taken from us.

“And so Ch’gran spearheaded the construction of seven great ships. On the anniversary of the Hur’q’s arrival on Qo’noS, Ch’gran ventured forth to the black sky to conquer the stars on behalf of the Klingon peoples.”

“What happened?” the boy asked, enraptured.

In a surprisingly low whisper, Father said, “No one knows. Their last words were that they found a world on which to plant our flag. But that was all they said, and then Ch’gran and his seven mighty vessels disappeared, never to be heard from again.”

“Not quite never,” Mother said with an indulgent smile. “One ship was found drifting in the Betreka Nebula, and some say that the other ships were somewhere in that sector.”

“Perhaps. But the location of the other six ships, and of the colony itself, remains one of the great mysteries of the Empire.”

Wide-eyed, the boy said, “They never found it?”

“No, my son—at least not yet. Now finish your lIngta’. It is time to sleep.”

The boy wolfed down the rest of his meat, then prepared his bedroll. After doing so, he turned to his parents. “Mother? Father?”

“Yes, son?” they said in unison.

“Some day, I will grow up to be the greatest warrior in the Empire and I will find the Ch’gran colony!”

Again, Father laughed, this time so hard that the boy was sure that no game animal would come within half a qelIqam of the tent for the next several turns. “Of that, my son, I have no doubt at all. But for now, sleep. Tomorrow, we shall return home and tell your sister and brother of your first hunt.”

Content with the day’s accomplishments, the boy drifted off to sleep. He dreamt of finding the Ch’gran colony and bringing it home to Qo’noS in much the same way he brought the lIngta’ back to the tent. Today he proved himself a hunter, and some day he would be the finest hunter of all, and bring glory to the Empire…

Part 1

Sound! Sound!

My Loud

War—Trumpets

2328

Chapter 1

Central Command

Vessel Sontok

“Entering standard orbit around the fifth planet.”

Standing in the center of the bridge of the Cardassian survey vessel Sontok, Gul Monor clasped his hands behind his back. “Excellent. Full sensor scan, Ekron. I want confirmation of those zenite readings.”

“Yes, sir.” Glinn Ekron manipulated a few commands on his console, situated just below and perpendicular to Monor’s command chair, which was on a raised platform at the bridge’s rear. The console’s lighting illuminated Ekron’s face, casting shadows that were accentuated by his unusually thick facial ridges. Monor thought the ridges made his second-in-command look like the statue on the grave of Monor’s father—which of course looks nothing like Father, but what do you expect from those idiots who call themselves sculptors these days? The shadows on Ekron’s face actually were an improvement, as it cut down on the resemblance to the statue. Monor’s father, of course, looked much more noble in life—he had a good, strong Cardassian face. Ekron, on the other hand, just had an ordinary face, one that didn’t stand out in the least. Nobody would ever notice that face, except maybe to comment on how thick the ridges were. Occasionally, Monor cared enough to wonder whether or not Ekron cultivated that.

The glinn announced, “Preliminary sensor data does verify long-range readings. This world is rich in zenite.” That mineral was used to combat botanical plagues, and was vital to the continued efficacy of several Cardassian farming colonies.

Hope in his voice, Monor asked, “Any life signs?”

“None so far, sir.”

Monor sighed. “Ah, well. I suppose that’ll make annexing it easier. Still, it’d be nice to not have to import a labor force to mine the stuff.”

“I’m sure that’s true, sir,” Ekron said.

“Assuming this isn’t another one of those damned sensor ghosts. Damned equipment’s never totally reliable, is it, Ekron?”

“No, sir, it isn’t.”

The gul started pacing the length of the Sontok’s bridge, moving away from the command chair, past Ekron’s operations console, as well as the navigation and tactical stations. The cramped confines did not allow him much room to have a proper pace. It was a failing in the design of the Akril class of ships, to Monor’s mind. “Ekron, make a note for me to send a memo to Central Command complaining about the amount of floor space on the bridge.”

“Yes, sir.”

“But not the lighting. I like the lighting.” Again, he sighed. “In any case, what we need is more reliable equipment. We could probably learn a thing or two from the Federation about sensors. They always seem to be one step ahead of us on that. Amazing, for such a backward people. No conception of how to run a government, for one thing.” Monor grew tired of pacing, and finally decided to sit in the command chair. “Though at least they have manners, for the most part. The humans, anyhow, and the Vulcans, of course, and those Betazoids. Tellarites, now they’re another story. How soon until the scan’s complete?” He stepped up the two stairs of the platform and sat in his chair.

Ekron glanced down at his console. “The full scan of the northern continent will be complete in one hour, sir.”

“Good. That’s what I like to hear.” Monor shifted position in his chair; it let out a squeaking sound. Now he remembered why he had gotten up from the chair in the first place. “Ekron, make a note to have that chair fixed.”

“I’ve already informed engineering of your problems with the chair, sir, but that is the standard command chair for an Akril-class vessel.”

“Damned excuses. Hiding behind standards like that. In my day, engineers knew how to fix things—how to make them better, not just make them adequate. They just don’t make ’em like they used to, Ekron.”

“No, sir, they don’t.”

Monor clambered out of his chair, and it made another squeak. “Tell them at least to get rid of that wretched squeaking noise. I assume that isn’t standard?”

“I’m sure it isn’t, sir.”

Nodding, Monor once again clasped his hands behind his back. “I should

damn well hope not. If we’re going to add this world to the Union, we need a vessel in top condition, not one with squeaking chairs. It’s unseemly, dammit. Cardassia isn’t going to be able to survive in this galaxy without resources, and that means we need zenite. And people to mine it. You sure there aren’t any life signs?”

“Only plant life and lower-order animals, sir. No indications of sentient life at all.”

Shaking his head, Monor once again started pacing. “Damn shame. That’s the nice thing about Bajor—lots of uridium and a population we can put to good use. Nice spiritual people, too, Bajorans. Much easier to take control of. Well, in theory, anyhow. I mean, the Klingons are pretty spiritual, too, but I wouldn’t want to try to conquer them. At least, not yet. Have we gotten any new reports from Bajor, Ekron?”

Ekron looked up from his console. “Nothing since last week, sir. As far as I know, the new government has been set up and Bajor has officially been annexed, but I’m not completely sure. I can put in a message if you want—”

Waving his arms, Monor said, “No, no, that won’t be necessary. We’ll get a dispatch soon enough. Central Command’s usually good about that sort of thing. Mostly, anyhow, when it serves their purpose. Long as the Obsidian Order isn’t involved, anyhow. Damn bunch of voles, the Order.”

“Uh, yes, sir.”

Frowning, Monor looked over at Ekron. Something sounded wrong with the glinn, like he wasn’t paying full attention. That was unusual, in and of itself, so Monor assumed something else distracted him. “What is it, Ekron?”

“We’re picking up something odd.”

Since neither sitting nor pacing was doing him much good, Monor decided to walk over to Ekron’s console. He stared at the readouts, which were utterly meaningless to him—not aided by the intensity of the light from the console. Monor had to blink the spots out of his eyes as he looked over at Ekron. “What do you mean by odd?”

Alien

Alien Miracle Workers

Miracle Workers Articles of the Federation

Articles of the Federation Supernatural Heart of the Dragon

Supernatural Heart of the Dragon War Stories: Book Two

War Stories: Book Two The Zoo Job

The Zoo Job Under the Crimson Sun

Under the Crimson Sun Breakdowns

Breakdowns Mermaid Precinct (ARC)

Mermaid Precinct (ARC) Supernatural 1 - Nevermore

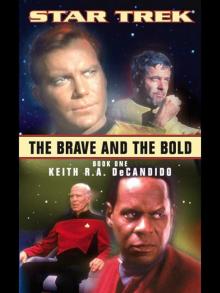

Supernatural 1 - Nevermore STAR TREK - The Brave and the Bold Book One

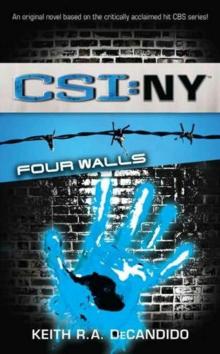

STAR TREK - The Brave and the Bold Book One Four Walls

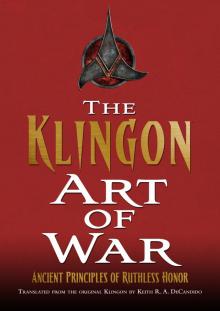

Four Walls The Klingon Art of War

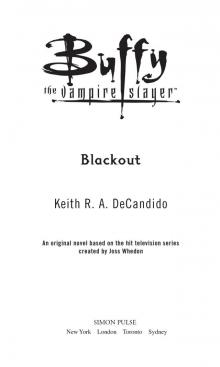

The Klingon Art of War Blackout

Blackout War Stories: Book One

War Stories: Book One The Brave and the Bold Book Two

The Brave and the Bold Book Two Honor Bound

Honor Bound Sleepy Hollow: Children of the Revolution

Sleepy Hollow: Children of the Revolution Worlds of Star Trek Deep Space Nine® Volume Three

Worlds of Star Trek Deep Space Nine® Volume Three Star Trek: TNG: Enterprises of Great Pitch and Moment

Star Trek: TNG: Enterprises of Great Pitch and Moment Genesis

Genesis Demons of Air and Darkness

Demons of Air and Darkness Star Trek - TNG - 61 - Diplomatic Implausibility

Star Trek - TNG - 61 - Diplomatic Implausibility Gryphon Precinct (Dragon Precinct)

Gryphon Precinct (Dragon Precinct) THE XANDER YEARS, Vol. 1

THE XANDER YEARS, Vol. 1 Nevermore

Nevermore Thor

Thor The Brave And The Bold Book One

The Brave And The Bold Book One I.K.S. Gorkon Book Three

I.K.S. Gorkon Book Three STARGATE SG-1: Kali's Wrath (SG1-28)

STARGATE SG-1: Kali's Wrath (SG1-28) Bone Key

Bone Key Guilt in Innocece

Guilt in Innocece Star Trek - DS9 Relaunch 04 - Gateways - 4 of 7 - Demons Of Air And Darkness

Star Trek - DS9 Relaunch 04 - Gateways - 4 of 7 - Demons Of Air And Darkness The Art of the Impossible

The Art of the Impossible I.K.S. Gorkon Book One: A Good Day to Die

I.K.S. Gorkon Book One: A Good Day to Die Under the Crimson Sun (the abyssal plague)

Under the Crimson Sun (the abyssal plague) DIPLOMATIC IMPLAUSIBILITY

DIPLOMATIC IMPLAUSIBILITY Tales from the Captain's Table

Tales from the Captain's Table A Burning House

A Burning House Cycle of Hatred (world of warcraft)

Cycle of Hatred (world of warcraft) Have Tech, Will Travel

Have Tech, Will Travel Security

Security