- Home

Page 3

Page 3

Alien

Alien Miracle Workers

Miracle Workers Articles of the Federation

Articles of the Federation Supernatural Heart of the Dragon

Supernatural Heart of the Dragon War Stories: Book Two

War Stories: Book Two The Zoo Job

The Zoo Job Under the Crimson Sun

Under the Crimson Sun Breakdowns

Breakdowns Mermaid Precinct (ARC)

Mermaid Precinct (ARC) Supernatural 1 - Nevermore

Supernatural 1 - Nevermore STAR TREK - The Brave and the Bold Book One

STAR TREK - The Brave and the Bold Book One Four Walls

Four Walls The Klingon Art of War

The Klingon Art of War Blackout

Blackout War Stories: Book One

War Stories: Book One The Brave and the Bold Book Two

The Brave and the Bold Book Two Honor Bound

Honor Bound Sleepy Hollow: Children of the Revolution

Sleepy Hollow: Children of the Revolution Worlds of Star Trek Deep Space Nine® Volume Three

Worlds of Star Trek Deep Space Nine® Volume Three Star Trek: TNG: Enterprises of Great Pitch and Moment

Star Trek: TNG: Enterprises of Great Pitch and Moment Genesis

Genesis Demons of Air and Darkness

Demons of Air and Darkness Star Trek - TNG - 61 - Diplomatic Implausibility

Star Trek - TNG - 61 - Diplomatic Implausibility Gryphon Precinct (Dragon Precinct)

Gryphon Precinct (Dragon Precinct) THE XANDER YEARS, Vol. 1

THE XANDER YEARS, Vol. 1 Nevermore

Nevermore Thor

Thor The Brave And The Bold Book One

The Brave And The Bold Book One I.K.S. Gorkon Book Three

I.K.S. Gorkon Book Three STARGATE SG-1: Kali's Wrath (SG1-28)

STARGATE SG-1: Kali's Wrath (SG1-28) Bone Key

Bone Key Guilt in Innocece

Guilt in Innocece Star Trek - DS9 Relaunch 04 - Gateways - 4 of 7 - Demons Of Air And Darkness

Star Trek - DS9 Relaunch 04 - Gateways - 4 of 7 - Demons Of Air And Darkness The Art of the Impossible

The Art of the Impossible I.K.S. Gorkon Book One: A Good Day to Die

I.K.S. Gorkon Book One: A Good Day to Die Under the Crimson Sun (the abyssal plague)

Under the Crimson Sun (the abyssal plague) DIPLOMATIC IMPLAUSIBILITY

DIPLOMATIC IMPLAUSIBILITY Tales from the Captain's Table

Tales from the Captain's Table A Burning House

A Burning House Cycle of Hatred (world of warcraft)

Cycle of Hatred (world of warcraft) Have Tech, Will Travel

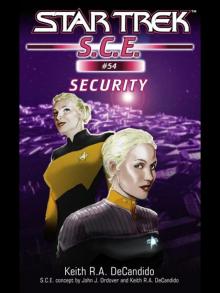

Have Tech, Will Travel Security

Security